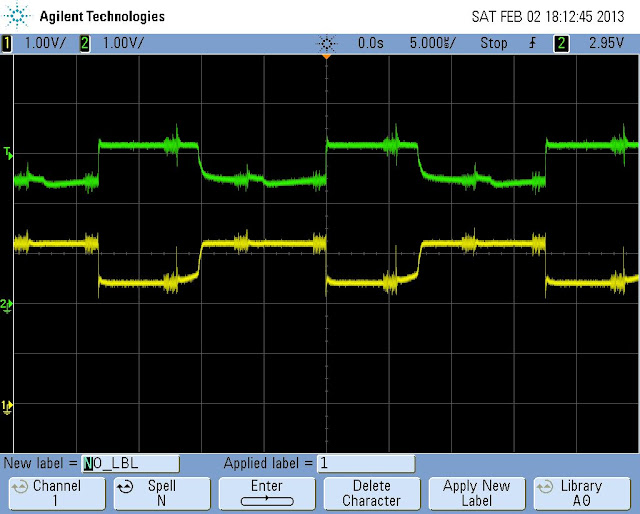

I already explained that I use Bit Angle Modulation (BAM) in contrast to Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) in the logic which controls the brightness of individual LEDs in my LED Cube. During the implementation of the brightness routines in my source I realized that it worked pretty as expected at high refresh frequencies but I got very weird results for lower refresh rates.

Especially if I set the brightness to 50% (decimal 128) the LED had a clearly visible on/off-pattern of 4Hz in when running the cube at 1kHz. The explaination of this is pretty straigtforward: when the brightness is 128, standard BAM causes the LED to be active 50% of a full 256-cycle. 1kHz has ~4 full cycles and therefore the LED turns on and off ~4 times/sec.

Wouldn’t it make more sense to have the LED alternate on each refresh, so that the average brightness is still 50% but the LED turns on and off with a period of two refreshes instead of 256? Similar to PWM but without the requirement for very high modulation rates?

My overall solution to tackle this issue was to add a simple counter which is increased with each refresh. When it reaches its maximum at 256 it’s reset to 0 again. I use this counter to look up a bit-value in a table, which results in the bit to check for in the brightness value in each cycle. I then use this bit to AND it to every single brightness value of each LED and if it’s non-zero the LED is turned on for this refresh. The initial values for this lookup table indicate the bit-values and resulting on-time for each bit of the brightness value. See the original code here. Of course this version still suffers from the problem described above, if the value is 50% the LED is on for the last 128 cycles of the 256-cycle period which leads to a slow and visible on/off blinking effect at low refresh rates.

The remedy for this is simple though, as the check-values are already in a lookup table. Just distribute the check-values much more evenly in the table and split up the connected on-time for each BAM-bit across the 256-cycle period. The resulting table is this. In this table every bit-value is strictly evenly distributed and spaced relative to each other so that the same values always have the same period.

The result of this change, which involved the usage of some LibreOffice Calc trickery, now allows for much smoother brightness control at much lower frequencies. Though there are limits to this. If the brightness is 1, it will still cause a visible 4Hz blinking at 1kHz refresh rate of the cube. There’s no way around this besides limiting the minimum refresh rate to higher values. But in contrast to expensive PWM and unmodified BAM modulation, this variant should reach a relatively regular ~32Hz flickering already at a brightness as low as 8 (~3%).

So in pseudocode the looping and brightness algorithm for the LEDs works as following:

int counter = 0;

int bamBit = 0;

while (true) {

// calculate if each LED is on or off during this refresh

bamBit = getBamBit(counter); // get current BAM bit from lookup table

for(int layer=0; layer<COUNT_LAYERS; ++layer)

for(int x=0; x<COUNT_X; ++x)

for(int y=0; y=COUNT_Y; ++y)

ledsActive[x][y][layer] = ledBrightness[x][y][layer] & bamBit;

// display this refresh

displayCube(ledsActive);

// reset counter at end of whole modulation period

if(counter > 255)

counter = 0;

}Update: I’m not sure if this really works in practice as it should in theory. Until today I’ve used a not perfectly even distributed version of the lookup table (see this version) which I smacked together by just mixing up the values in a much simpler way (splitting the blocks and putting them together in a more distributed fashion) which was much quicker to come up with. Nevertheless I have the impression that the flickering has not smoothened at lower refresh rates and brightnesses as expected. I’ll have to look into that sometime in the future again and make a better comparison of both versions. But yet it’s still much better than the unmodified BAM brightness algorithm.